Media, Bloviate Much?: The Constitutional Reality of Trump v. V.O.S. Selections, LRI

A Targeted Ruling, Not a Wholesale Bar

For the next few days, the airwaves and social feeds will be saturated with “historic” proclamations regarding the Supreme Court’s 6–3 decision in Trump v. V.O.S. Selections, Inc.. Depending on the outlet, the ruling is either a “disgrace” that “disarms” the presidency or a “landslide victory” for the rule of law. However, if we strip away the sensationalist Trump narrative designed for clicks, we find a decision that is far more technical and clinically focused on statutory boundaries than the headlines suggest.

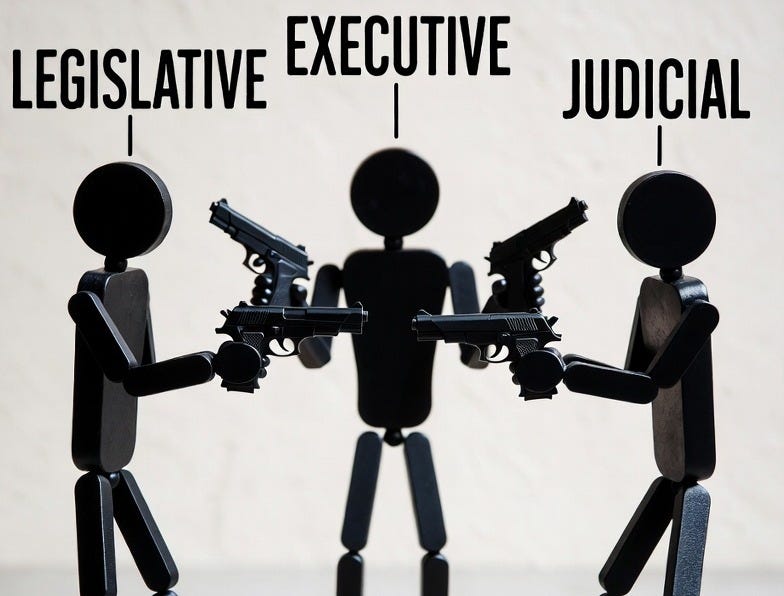

While every Supreme Court decision is a vital component of our constitutional function, this ruling should not be overinterpreted. To understand the impact of the February 20, 2026, opinion, we must look past the political noise and focus on three fundamental truths: the ruling is limited to a specific legal mechanism; it centers on a technical check of executive taxing power; and it demonstrates that our system of checks and balances is functioning exactly as designed.

1. A Targeted Ruling, Not a Wholesale Bar

The first and perhaps most critical point is that this ruling applies to a very specific legal mechanism: the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA). It does not, by any stretch, bar the President or the executive branch from imposing tariffs through other means.

The administration’s “Liberation Day” agenda relied on IEEPA to bypass the procedural hurdles found in traditional trade laws. The Supreme Court held that the phrase “regulate importation” in that specific 1977 sanctions law does not grant a “blanket license” to levy taxes. However, the majority opinion, written by Chief Justice John Roberts, carefully distinguished IEEPA from the vast array of other statutes within Title 19 of the U.S. Code where Congress has explicitly delegated tariff authority.

For instance, the ruling does not touch the President’s power under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which allows for duties to protect national security. It does not affect Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, which permits tariffs to remedy unfair foreign trade practices. It also leaves open Section 122 of the 1974 Act, which specifically addresses “monetary crises” and balance-of-payments deficits. In fact, the administration has already signaled a “backup plan” to pivot to these alternative pathways.

In comparison to sweeping decisions that reorder the constitutional relationship between branches, this is a surgical intervention. It caps the “IEEPA pen,” but it does not remove the President from the trade arena; it merely mandates that he use the specifically tailored statutory tools provided by Congress, some of which come with mandatory investigations and public comment periods .

2. The Power of the Purse vs. Foreign Affairs

The core of the legal dispute was not whether the President can conduct foreign affairs, but whether he can unilaterally redefine what it means to “regulate” versus what it means to “tax”. The media has framed this as a personal rebuke of President Trump, but legally, it was a check on the Executive branch’s attempt to expand its interpretation of taxing power—an interpretation that was an outlier in fifty years of IEEPA history.

Chief Justice Roberts grounded the decision in Article I, Section 8, Clause 1: “The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises”. The administration argued that because tariffs can be used to “regulate” trade, the power to regulate importation under IEEPA must include the power to tariff. The Court decisively rejected this “interpretive contortion”.

Roberts noted that while taxes may accomplish regulatory ends, they are not synonyms for regulation. In every other instance where Congress has delegated tariff powers, it has done so explicitly, using words like “duty” or “tariff” and setting strict limits on rates and duration. The fact that, for half a century, through eight different administrations, no President had ever read IEEPA to permit tariffs was, for the Court, a “telling indication” that the power did not exist.

This is a structural win for the Madisonian commitment to decentralized power. It clarifies that even the President’s role as the “sole organ” of foreign affairs does not permit him to rewrite the tax code without a clear and explicit mandate from the people’s representatives in Congress. It is what the electorate and the President would have expected from a majority textualist and originalist Court.

3. The Functioning of Checks and Balances

Finally, the most significant takeaway from Trump v. V.O.S. Selections is that the government is functioning properly in terms of checks and balances . The ruling is a textbook application of the “Youngstown” framework, which posits that presidential power is at its “lowest ebb” when it is incompatible with the expressed or implied will of Congress.

By invoking the “major questions doctrine,” the Court performed its essential role in preventing the executive from using ambiguous language in a decades-old sanctions law to launch a “transformative” expansion of its authority. The doctrine requires that if Congress wants to delegate power over issues of vast economic or political significance—such as a $3 trillion tariff shift—it must say so clearly .

Furthermore, the judiciary provided a balanced set of outcomes that avoided the “total disarmament” narrative. While specific tariffs were ruled illegal, the Court vacated the “universal injunctions” that had been issued by lower courts. Relying on the 2025 precedent of Trump v. CASA, Inc., the Court held that federal judges generally lack the authority to issue nationwide relief that extends beyond the specific parties in a case. This provides the administration with a “procedural soft landing,” as the refund process for an estimated $175 billion to $200 billion in collected duties will now be handled through the specialized Court of International Trade (CIT) on a case-by-case basis.

This centralization of litigation in the CIT ensures that trade law maintains a “necessary degree of uniformity” while still checking executive overreach. The ruling doesn’t represent a judicial coup or a political opposition; it represents the Court performing its duty to ensure that major policy shifts remain tethered to the legislative process.

Constitutional Equilibrium

The 2026 ruling is a definitive affirmation of the principle that there can be no “taxation without representation”. It restores the boundary between economic statecraft and the legislature's fundamental fiscal powers.

The sensationalist narrative of a major blow to the presidency misses the technical reality: the President remains the primary actor in foreign affairs and retains a vast arsenal of trade tools. However, these tools must now be wielded with the precision and transparency required by the Title 19 statutes that were designed for them, rather than the broad-brush “emergency” framework of IEEPA. In the end, the noise of the media cycle fades against the clinical reality of a constitutional system successfully recalibrating its own scales.