Child Poverty Orphans, Redistributionism, and the Axis of Dependency

The Trade-offs of Dependency Architecture

The intersection of humanitarian impulse and institutional persistence has created a global paradigm where poverty is no longer merely a condition to be alleviated but an industry to be managed. At the heart of this complex lies a profound contradiction: the very systems designed to save the impoverished frequently dismantle the local structures required for self-sufficiency, replacing them with a state of perpetual, vertical dependency. This phenomenon is most poignantly encapsulated in the experience of Shelley and Corrigan Clay, an American couple whose journey to Haiti serves as a definitive case study in the unintended consequences of the redistributionist mindset.

The Clays arrived in Haiti with the altruistic intent to adopt a child and establish an orphanage. During the process, they learned that the child they intended to adopt actually had a parent who would visit multiple times, bringing the child food and small gifts. When they asked the orphanage and eventually the mother why she had brought her child there, her answer was a window into the systemic failure of aid: she loved her child deeply but had no job and therefore no money to buy them food, and they lived in a lawless, gang-infested part of town. The couple realized with dismay that they were prepared to spend $20,000 on the adoption process. That is, the sum is almost entirely consumed by consultants, administrative overhead, and markup. In Haiti's economic context, the same $20,000 would have been sufficient for the mother to raise her child to adulthood. This realization—that they were participating in a system that was effectively creating orphans by capitalizing on (therefore, sustaining) parental poverty rather than alleviating it serves as the primary metaphor for the broader poverty industrial complex.

The Mechanics of the Poverty Industrial Complex

The poverty industrial complex refers to the multibillion-dollar network of NGOs, government agencies, and international contractors that have turned poverty alleviation into a highly consolidated business. While these organizations are often staffed by individuals with good hearts, the systemic incentives under which they operate prioritize institutional survival and administrative rent over actual economic outcomes. It is the opposite of good in any sense of the word.

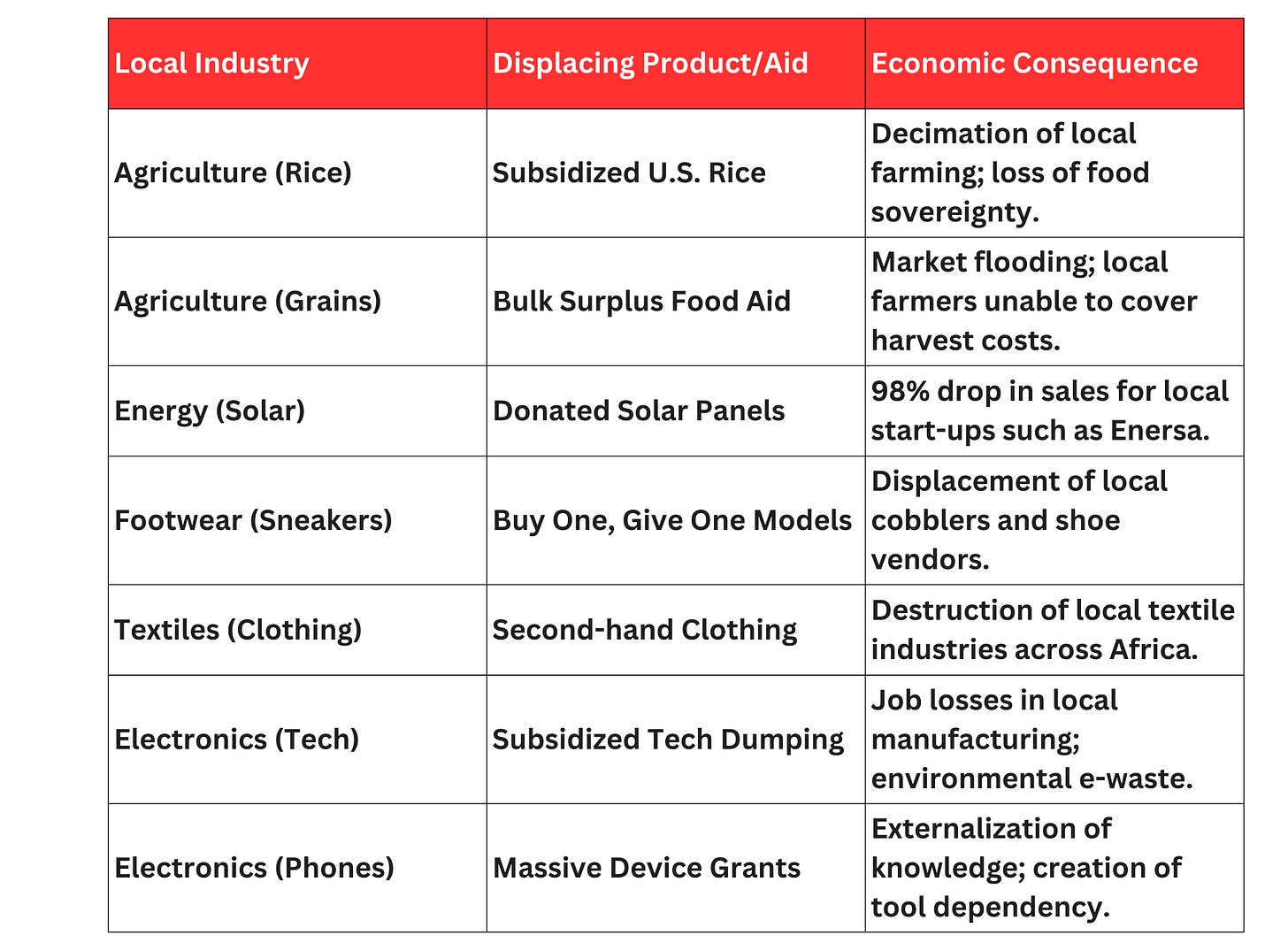

One of the most destructive elements of the poverty industry is the influx of subsidized or free goods into developing markets. Whether in the form of food aid, clothing, or technology, these donations create a supply shock that local producers cannot survive. When the West gives what a local entrepreneur is trying to sell, it effectively kills the market.

Figure 1:

The destruction of the Haitian rice industry remains perhaps the most cited example of this failure. In the 1990s, the Haitian government was pressured to slash tariffs on imported rice, a move championed by the Clinton administration. This allowed heavily subsidized rice from Arkansas to flood the Haitian market (Figure 1). While it provided temporarily cheaper food, it drove thousands of farmers off their land and into the overcrowded slums of Port-au-Prince. Bill Clinton later admitted the catastrophic nature of this policy, noting that it had not worked and was a mistake that he had to live with every day, as it cost Haiti its capacity to feed its own people. Clinton’s admission highlights the devil’s bargain inherent in redistributionism: short-term relief in exchange for long-term structural collapse.

Administrative Rent and the Intermediary Function

Administrative rent describes the portion of aid funding that never leaves the donor country’s economy, instead being captured by high-level consultants and implementing partners. In the United States, the majority of foreign assistance funding is awarded to a small group of large contractors based in and around Washington, D.C., colloquially known as Beltway Bandits.

"The poor are often treated as objects of charity, as passive recipients of aid. But real development happens when people are recognized as the primary agents of their own destiny. The aid industry often ignores the local entrepreneur in favor of the 'helpless' victim."

—Obadias Ndaba, Rwandan Jouralist and Advocate

Research into USAID spending reveals a highly consolidated industry. As of 2017, approximately 60 percent of all USAID funding was directed to just 25 groups. By 2022, the concentration had intensified, with 10 contractors winning more than 50 percent of every contract dollar. This industrial aid complex functions through an intermediary system where international partners register themselves locally to appear aligned with localization agendas, yet they retain the vast majority of the funds for overhead, salaries, and administration. They often hire local companies to do the most difficult, on-the-ground parts of the process but pay them significantly lower rates, keeping the difference as profit. Those local companies, robbed of the full capital injection, are unable to reinvest in local development and business growth. Furthermore, this intermediary function robs in-country leaders of direct contact with the people in need, as the accountability loop is vertically oriented toward Washington, D.C.

Outcome Blindness and Administrative Persistence

A critical question arises: why do these systems of aid and intervention persist if their failure is so well-documented? The answer lies in the concept of administrative persistence and outcome blindness. Public administration is inherently designed to generate activity, spend budgets, and produce reports, but it is often fundamentally blind to the actual downstream consequences of its programs.

The Incentive to Ignore Failure

Bureaucratic organizations are structured for durability and risk avoidance rather than effective problem-solving. In the context of the poverty industry, an agency’s success is often measured by its ability to secure additional funding, expand its mandate, or comply with complex procedural requirements, rather than its success in lifting people out of poverty.

In an environment of outcome blindness, failure is rarely treated as a signal to redesign or terminate a program. Instead, failure frequently becomes a justification for expansion. If a project fails to improve local conditions, the administrative response is typically that the project was underfunded or too limited in scope, leading to a request for more resources. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle where the persistence of the organization is decoupled from the achievement of its stated goals, reinforcing a vertical, paternalistic dependency axis.

Symbolic Equity vs. Actual Capacity Building

This blindness is further exacerbated by a focus on symbolic equity—visible policy levers that appear to address injustice but ignore the root causes. In foreign aid, this manifests as a focus on participation and expenditure as proxies for effectiveness. For example, an agency may report success because it distributed 10 million cell phones or achieved a certain completion rate for a training program. However, these metrics are process-oriented; they do not measure whether the phone distribution actually facilitated economic growth or if the training led to stable employment.

“Aid has been, and continues to be, an unmitigated political, economic, and humanitarian disaster for most parts of the developing world... It has fostered a culture of dependency and corruption, and has encouraged the belief that the poor are victims to be ‘saved’ rather than partners to be engaged.”

—Dambisa Moyo, Zambian Economist and author of “Dead Aid.”

The broken information feedback loop is the structural cause of this blindness. In a traditional market, the customer—the person receiving the service—provides the feedback that keeps the provider accountable. In the aid industry, the customer is the donor taxpayer in the West, while the beneficiary is the person in the developing world. Because the beneficiaries cannot fire the aid agency or vote against its funding in the donor country’s elections, the agency has no systemic incentive to correct its errors based on the actual outcomes on the ground.

Structural Barriers: The Missing Foundations of Prosperity

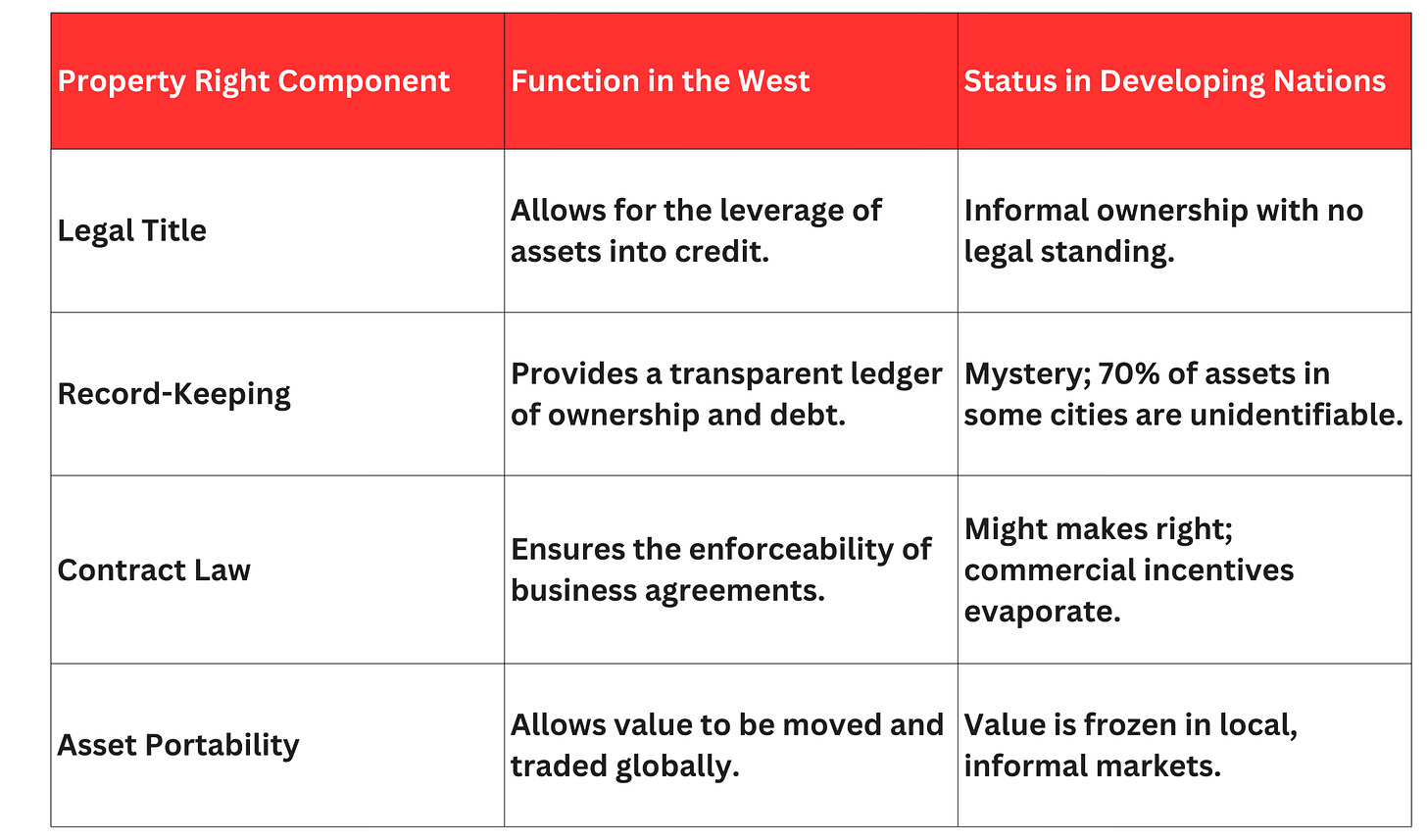

The liberal redistributionist mindset ultimately robs populations of dignity and self-determination by treating them as poor and underrepresented rather than as potential creators of value. While the industry focuses on handouts, it ignores the structural foundations of economic mobility: public safety, justice systems, property rights, and the ability to start a business (Figure 2).

Property Rights and Dead Capital

Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto argues that the poor in developing nations save and possess an immense amount of assets—estimated to be forty times all the foreign aid received globally since 1945. However, these assets exist as dead capital because they are not legally documented. Without a legal title to their land or a formal registration for their business, an individual cannot use their home as collateral for a loan, cannot easily transfer ownership, and cannot access the legal protections required for large-scale investment.

Figure 2:

In the United States, the single most important source of funds for new businesses is the mortgage on a small business owner’s home. In contrast, entrepreneurs in places like Haiti are frozen out of this mechanism. The lack of a public and transparent ledger means that assets are suppressed from being used in formal business activities, forcing the poor to rely on traditional, hidden, and informal economies like bazaars, where scaling a business is impossible.

The Legal Gap

The lack of property rights is compounded by a justice system that fails to protect the powerless. When political authority fails to enforce contracts, the risks associated with starting a business become insurmountable for those with little margin for error. In these societies, the law ceases to be a guardian of justice and instead becomes a tool of power used by the elite to maintain privilege. This environment stifles entrepreneurship and normalizes bribery, as the formal path to prosperity is blocked by senseless laws and bureaucratic hurdles.

Nations as Social Orphan

The story of the social orphan is a metaphor for the entire developing world under the redistributionist model. By treating the poor as objects of charity rather than active protagonists, the poverty industry adopts entire nations, fostering a paternalistic relationship that mirrors the orphanage system.

"Instead of building us up, [the aid industry] created a lasting image of Africa that trades on pity, not power. It’s not only insulting. It’s demeaning, dehumanizing, and revolting. Poverty porn does nothing to promote African dignity…It creates a culture of dependency."

—Magatte Wade, Senegalese Entrepreneur and Director of the Center for African Prosperity

Data Manipulation and the Invention of Crises

To sustain this paternalism, the poverty industry often relies on data manipulation to create a sense of perpetual crisis. Anthropologist Timothy T. Schwartz has documented how humanitarian organizations like UNICEF and Save the Children sometimes inflate statistics to trigger donor responses. Following the 2010 Haiti earthquake, these organizations conjured images of over one million lost, separated, or abandoned children wandering through the ruins. In reality, the number of truly orphaned children was likely fewer than 1,000, and potentially as low as 100. Schwartz argues that the Haiti Orphan Crisis was a gold mine for organizations feeding untruths to the media, ensuring an avalanche of donations while burying the data that showed parents were simply too poor to provide food.

We have seen several twenty-year cycles intended to end hunger and poverty, and virtually all have failed to make the social changes necessary for self-determination. Breaking this cycle requires a shift from a redistributionist mindset to a framework of partnership and entrepreneurial capitalism.

The ultimate goal of a humanitarian endeavor should be its own obsolescence (a program design that Washington, DC, rarely, if ever, lets happen). By focusing on property rights, the rule of law, and the empowerment of local entrepreneurs, the West can stop treating countries as social orphans and start treating them as equal partners in the global economy.

As even Bono, the co-founder of ONE and a longtime activist, has acknowledged, the solution to poverty is not a handout but commerce.

“Aid is just a stub cap. Commerce, entrepreneurial capitalism, takes more people out of poverty than aid. Of course. We know that”.

—Bono